'Divine' - Craig Cameron-Mackintosh

Collection: 'Divine' - Craig Cameron-Mackintosh

Divine

Craig Cameron-Mackintosh

29.06.23 - 29.07.23

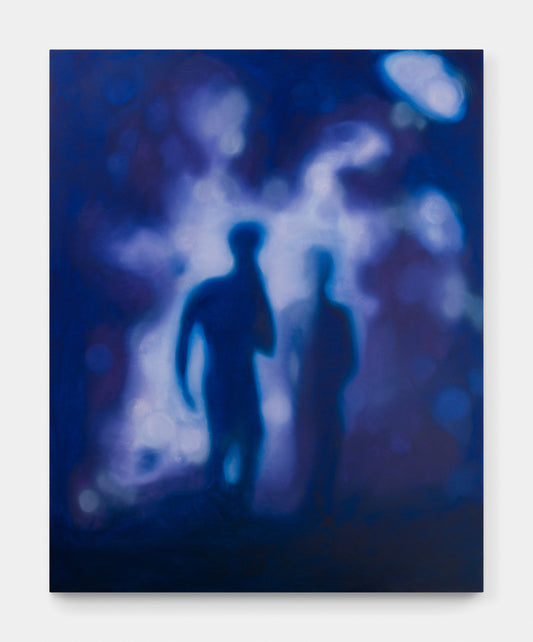

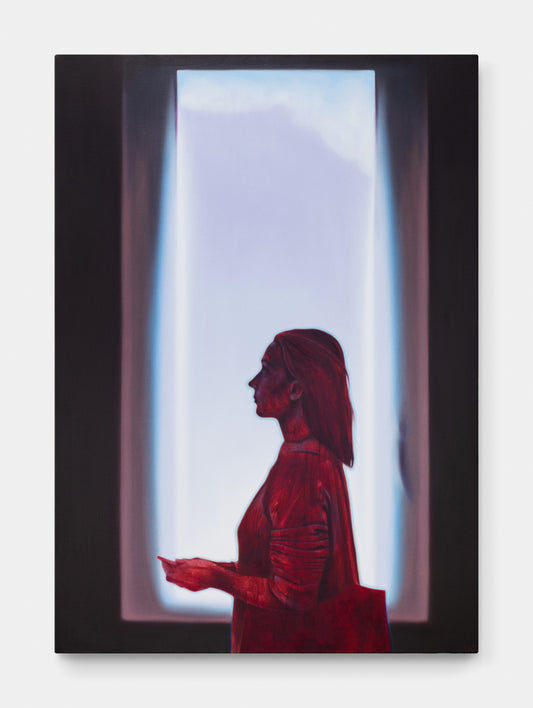

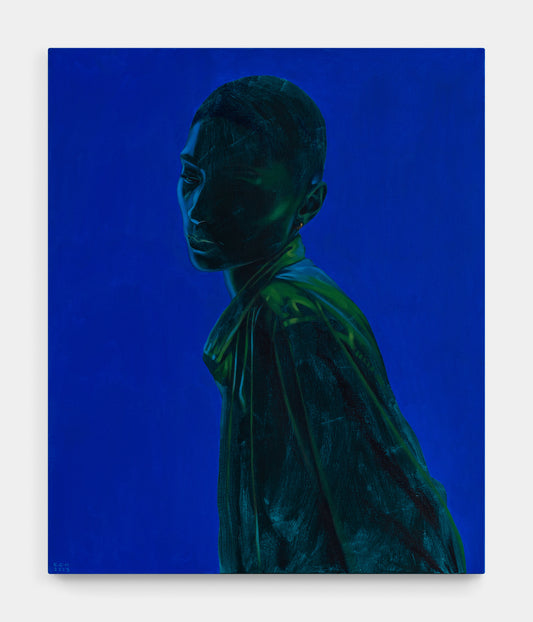

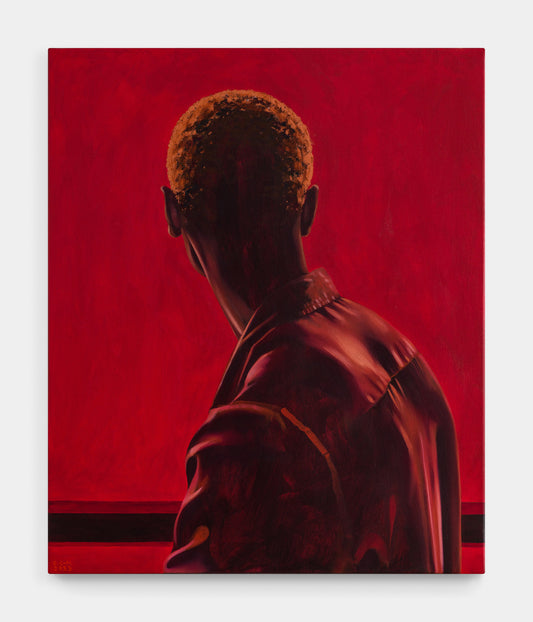

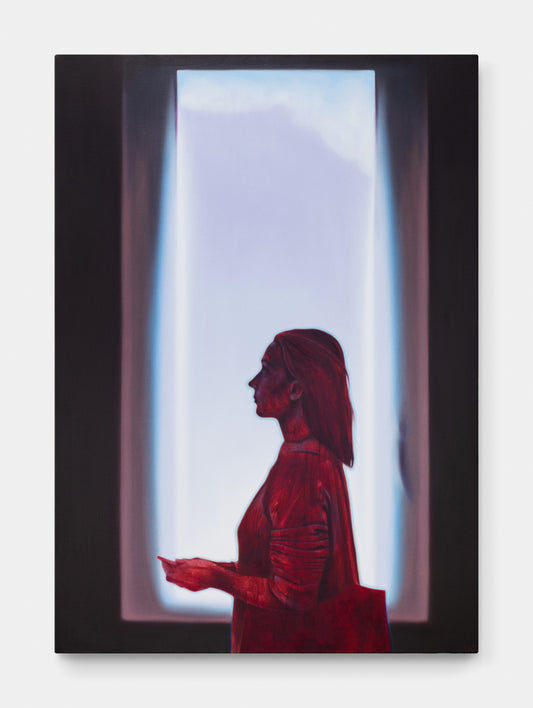

What can be seen in obscurity? The question is prompted by Craig Cameron-Mackintosh who, over the past few years, has become known for his portraits of models and friends in silhouette. They are always backlit, and they are almost always turning away from the viewer. Because they are painted realistically, as well as to scale, they have a presence. There is a sense that the figure is standing before us, here and now. But then, their features are obscure, their details omitted, their expressions hidden from view. When the figure turns away from us, she begs the question, “What is she looking at?” And then we see colour: vivid purples, vibrant blues, deep reds. The colour, too, has a presence. It hums.

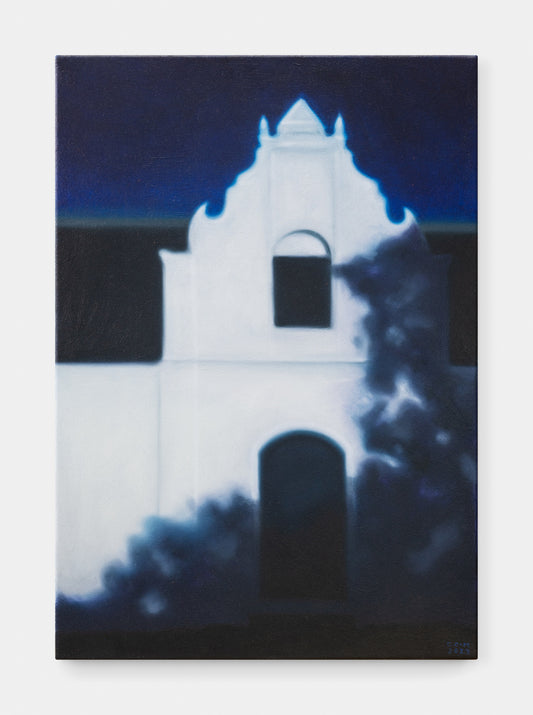

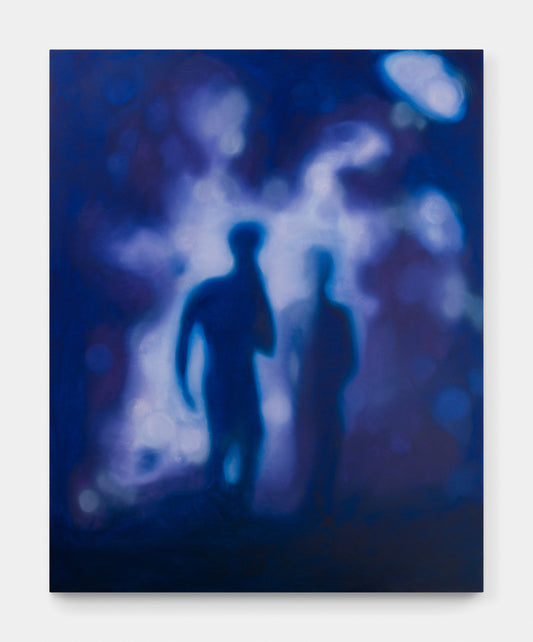

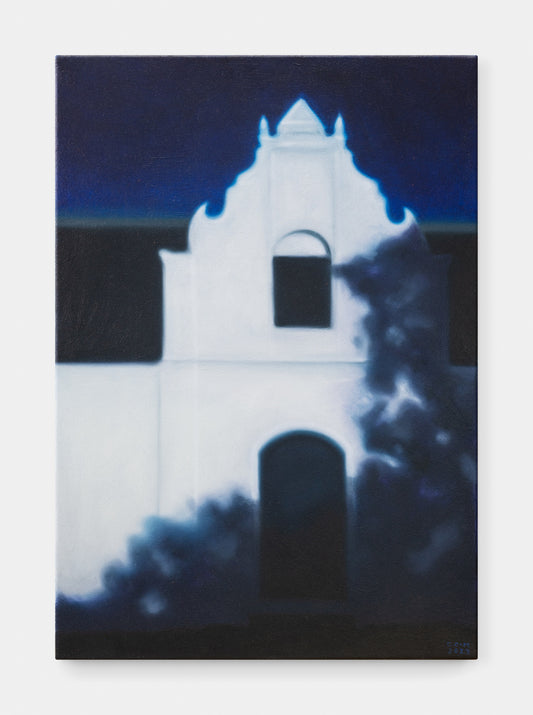

This line of inquiry has guided Cameron-Mackintosh into a new direction. These images are largely devoid of figures. Some are landscapes, others abstract. Like the portraits, they are based on photographs, but whereas the former are sharp and staged, the latter are blurry and spontaneous. As Cameron-Mackintosh puts it, he went foraging in his own archive, moved by those accidental images: blown-out, out-of-focus, overexposed. To him, these accidents are expressive. Of what, exactly?

Moving our eyes from painting to painting, portrait to landscape, landscape to abstract, the effect is somewhat cinematic. It is as if our eyes are lenses, and we are adjusting their apertures. Rather than achieving a crisp, clear image, however, we are asked to linger in obscurity. We are no longer in the realm of representation. We are in the realm of intuition. These images seem to have bubbled up from the unconscious. Or else they have floated down from the heavens. These luminous shadows, as the exhibition’s title professes, have a divine quality to them.

Cameron-Mackintosh admits that divine images have a prevalent place in his unconscious mind. As a student at an Anglican school, he was first exposed to art via religious iconography. Looking again at the portraits, we might recognise variations on the poses allocated to saints, or the sort of molten colours found on stained glass. Light functions as it does in religious paintings. Often, it has no logical origin. Where it does – when the light is pouring in from a window, or shining from a full moon – it is not diffuse, but exaggerated. The light – like the figures and colours – has a presence. As Cameron-Mackintosh describes it, light becomes a character. When it glows, it seems to speak.

Part of Cameron-Mackintosh’s intention with this exhibition is to strip this iconography, typically reserved for religious or spiritual paintings, down to the everyday. Whereas, in classical painting, lapis lazuli would have been a sacred colour, reserved only for the holiest of figures, Cameron-Mackintosh uses the same colour (or rather, its modern synthetic equivalent), liberally in backgrounds. The extravagantly gold and gilded frames used for important subjects like saints are repurposed and painted over for paintings of pure colour. The paintings that are the most vibrant or celestial – and thereby, by the logic of religious painting, the holiest – are actually close-ups of a sequin jacket and the folds of a shirt. Cameron-Mackintosh takes these mundane objects, these ordinary moments, and elevates them to the divine.

-Keely Shinners, 2023

Works on exhibition

-

Meant to Be

Vendor:Craig Cameron-Mackintosh (1987- )Regular price R 28,750.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sold

SoldReligious Experience

Vendor:Craig Cameron-Mackintosh (1987- )Regular price R 17,250.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sold

SoldShadow Garden

Vendor:Craig Cameron-Mackintosh (1987- )Regular price R 51,750.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Stained Glass

Vendor:Craig Cameron-Mackintosh (1987- )Regular price R 51,750.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sold

SoldEscarpment

Vendor:Craig Cameron-Mackintosh (1987- )Regular price R 46,000.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sold

SoldPatron Saint

Vendor:Craig Cameron-Mackintosh (1987- )Regular price R 80,500.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sold

SoldDe Goede Hoop

Vendor:Craig Cameron-Mackintosh (1987- )Regular price R 34,500.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Out of Body

Vendor:Craig Cameron-Mackintosh (1987- )Regular price R 40,250.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Saying Less, Meaning More

Vendor:Craig Cameron-Mackintosh (1987- )Regular price R 63,250.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Late, October

Vendor:Craig Cameron-Mackintosh (1987- )Regular price R 63,250.00Regular priceUnit price / per

More exhibitions

-

Investec Cape Town Art Fair 2023 | Main Section

Investec Cape Town Art Fair 16 – 19 February 2023 Cape Town...

-

Expo Chicago 2023

13.04.23 - 16.04.23Navy Pier, Chicago USABooth 414 EBONY/CURATED is proud to present...

-

'Nowhere Better to Be' - Craig Cameron-Mackintosh

Craig Cameron-Mackintosh’s debut solo exhibition ‘Nowhere Better to Be’ continues the artist’s...